Pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. It is sometimes very difficult to clarify the precise boundary between a state of health and a state of disease.

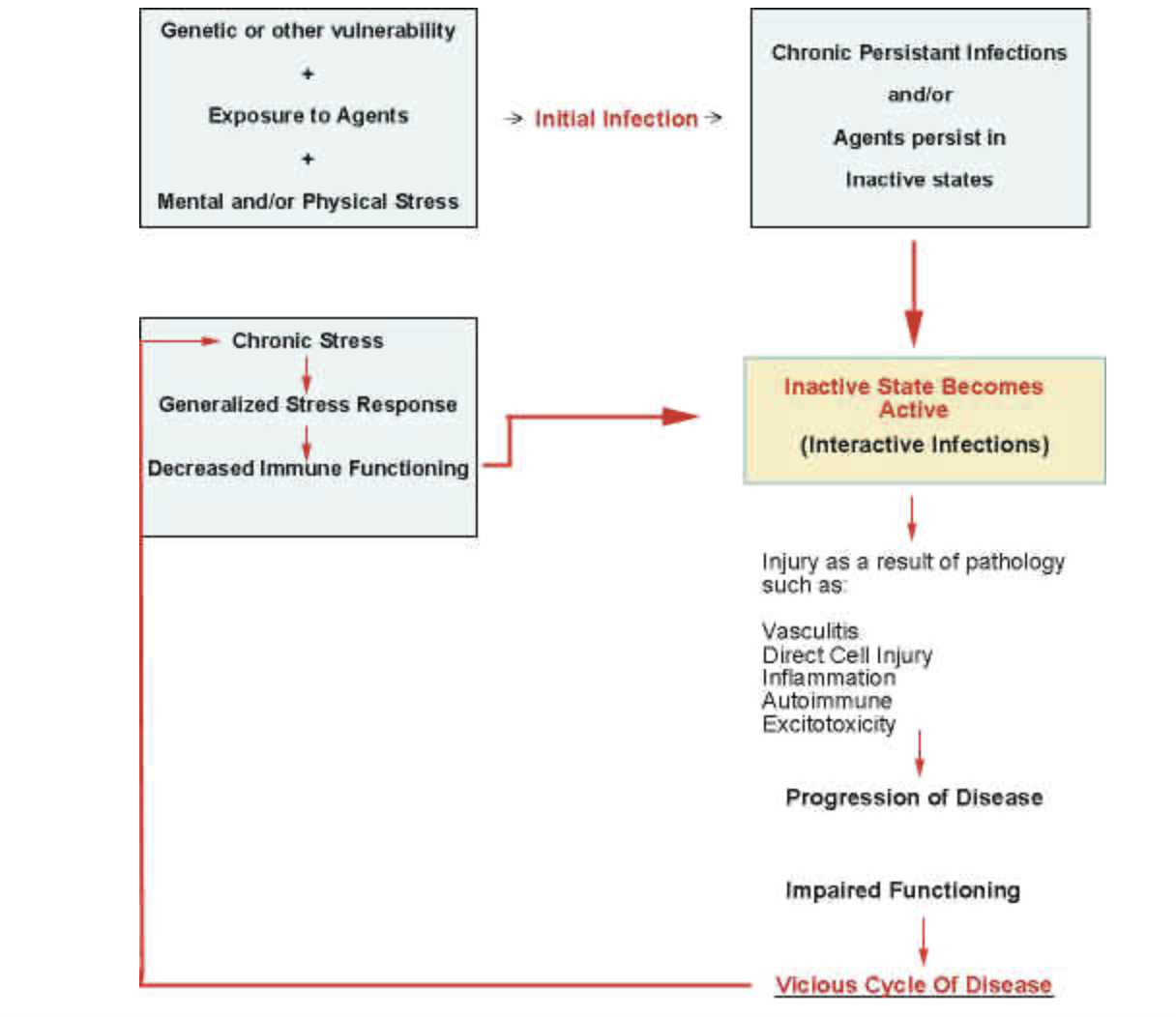

While health is a state of balance, disease is instead a state of imbalance. When viewed from a multi-system perspective, there is an imbalance between the contribution to disease and the deterrents to disease (diagram). This multi-system imbalance results in a pathological cascade (diagram). To understand this process, it is first necessary to understand each component of the pathological cascade. The proximate cause of disease can be viewed as an adaptive failure. It often begins with a state of extreme imbalance and is most often the result of the interaction between a vulnerability and a life circumstance. In some instances an extreme vulnerability alone or an extreme environmental circumstance alone many result in pathology.

In a state of health, there is an adaptive capacity to acquire and allocate a balanced ration of the resources needed for survival. An insufficient amount of any resource results in a deficiency, while an excess of a resource or anything else in the environment may be toxic. In a pathological state there is either a failure or a dysregulation of the capacity to acquire and allocate needed resources and to defend effectively against threats. In some instances there may be an impaired capacity to adequately discriminate between what is harmful or beneficial and/or an impaired capacity to respond with adequate adaptive specificity. This adaptive failure may be further magnified when a subsequent cascade of events causes further adaptive failure resulting in a disintegrative vicious cycle. In nature, there is a redundancy of checks and balance, which often acts as a safeguard preventing pathological processes. In addition, many weaknesses may be compensated by other stronger capabilities. Although constant change, stress, and distress are frequent events; pathology usually occurs only when there is an interaction of a vulnerability and a life situation that cannot be compensated because there is a sequence of failures of multiple regulatory systems which are often safeguards to disease.

Vulnerabilities to disease may be genetic, developmental and caused by prior trauma. There may be increased vulnerability associated with early and later life. A state of acute or chronic stress may increase vulnerability when resources are allocated to other functions. Genetic vulnerabilities must be understood in the context of evolution. Genetic vulnerabilities are far more common, while genetic defects are rare. True genetic defects which compromise adaptive functioning without any other benefit compromise reproductive success and tend to be rapidly reduced in the gene pool. Genetic defects are associated with a large number of rare conditions, but do not cause common widespread diseases, which affect large numbers of people

Genetic vulnerability to disease may be a result of the unique path of evolution or design compromises.* The unique path of evolution is determined by many unknown historical events. This has led to the development of genes, which have current adaptive value, being added to or replacing genes which had adaptive value in some prior environmental circumstance. This results in traits which may have no or little current adaptive value that are best understood from a greater understanding of the history of evolution.

Design compromises are traits, which have adaptive value in certain environmental circumstances that may compromise adaptive capacity in other life situations. A failure to appreciate this concept has results in many genetic vulnerabilities being mislabeled as genetic defects. Examples of these genes include sickle cell traits and the gene for cystic fibrosis, both of which afford some protection against infectious disease

Developmental vulnerabilities are a result of a past environmental circumstance, which caused trauma at a critical point in development. In general, trauma associated with earlier stages of development is associated with a greater adverse impact upon subsequent development. These traumatic events may include – a failure to acquire needed resources, toxic exposure and adverse consequences of infectious disease.

Trauma may often have a more severe impact upon the very young or very old than upon a mature adult. Trauma is sometimes associated with residual injury, which may cause dysregulation of adaptive functioning and contribute to increased vulnerability in the future.

Change in the allocation of resources in the body at times of stress contributes to disease in some instances. In a state of physiological stress, there is a shift in the allocation of resources which results in decreased environmental functioning and increased immune functioning (sickness behavior.) In a state of environmental stress, conversely there is a shift towards increased environmental functioning and decreased immune functioning. These changes in the allocation of resources are mediated by an interaction of the hormonal, nervous, and immune systems. Although acute stress is often well tolerated and beneficial chronic stress and/or a dysregulation of the stress response systems results in a prolonged imbalance in the allocation of resources which may contribute to increased vulnerabilities for functions which were compromised by a decreased allocation of resources.

*Nesse, Randolph. Why We Get Sick, The New Science in Darwinian Medicine, Times Books, Random House 1995.

Life situations, which contribute to disease, include lack of resources, toxic exposures, environmental extremes, and competition with other organisms.

An extreme lack of resources or toxic exposure results in obvious, and well recognized patterns of disease, while more subtle resource deficiencies and/or toxic exposure contribute to more cryptic disease syndromes. In either case, lack of resources and toxic exposure can result in increased vulnerability to other disease.

Although man has considerable flexibility adapting to environmental extremes, there are limits and extreme environments that may contribute to disease.

Some of our current pathology may be a result of our difficulty adapting to the changing environment caused by rapid technological changes. We are only a few hundred generations out of the Stone Age, a brief time from a evolutionary perspective, Although humans are highly adaptive to live in a broad range of environmental conditions, technological advances have caused a rapid change in our culture and physical environment – from the Stone Age through the Agricultural , Industrial, and now the Information Age revolutions. Although these changes have had many benefits, it has also led to a rapid environmental change resulting in changing patterns of disease.

Competition with other organism can contribute to disease and result in trauma that increases vulnerability to subsequent disease. Some of this competition is with in our own species for resources and mates. In addition we also compete with some other species, the most significant being microbes. Microbes possess a competitive advantage because they reproduce much more rapidly than humans. This difference affords microbes an opportunity to evolve adaptive capabilities faster than humans can evolve defenses. There is a never ending arms war between our defensive mechanisms and the invasive capability of pathogens*. Some disease is the result of injury from infectious disease resulting in vulnerability to other disease processes.

Mental Illness

In most cases, specific life situations combined with specific vulnerabilities lead to disease. Although many pathways of disease exist, the final pathways are often events that overwhelm adaptive capacity and/or cause adaptive mechanisms to go awry, leading to a pathological cascade of events resulting in a pathological vicious cycle. The pathological process may evolve and persist in multiple systems simultaneously.

“The mental jail, which may be defined as the subjective experience of life without meaning, hope or love, that feels like a prison, is far more confining. Its ceiling is too low to stand tall and proud; its walls too narrow to breathe easily; its cell to short to stretch out and relax. The sentence is indeterminate. It must be deconstructed, or suicide, homicide, or severe mental illness can result. The bricks of the mental jail are usually made of guilt and shame, rage and the need for sweet revenge, depression, fear, and feelings of worthlessness……..” (Tolstoy)

In a state of mental illness, mental functioning does not reflect the life situation and does not maintain balance by facilitating an adaptive allocation of resources, which may result in the failure to experience well being, pleasure, fulfilling relationships and productive activities and the mental flexibility to adapt to change and the ability to recognize and contend with adversity.

“Brain-related diseases and injuries are estimated to exceed over half a trillion dollars a year in health care, productivity, and other economic costs.” (NIMH statistic)

The brain regulates this allocation of resources and can be conceptualized in three fundamental regions – the cerebral cortex (cognition), the limbic system (emotional functioning), and the brain stem and hypothalamus (vegetative functioning). Cognition, emotional and vegetative functioning are all interactive systems. Some pathological conditions affect all three areas, while other conditions primarily affect specific areas.

Dysfunction of the cerebral cortex is associated with an impairment discriminating beneficial from harmful aspects of the environment and/or an impairment discriminating adaptive responses and the flexibility to respond quickly to changing environmental circumstances.

Dysfunction of the limbic system is associated with emotional reactivity that does not reflect the current life situation and impedes adaptation. The current mood facilitates adaptation by altering perception, processing, vegetative functioning, and behavior. In a state of health, mood reflects the life situation and facilitates adaptation (Figure 1). When threats exist, it is adaptive to experience negative or adversive mood states. Although the predominance of adversive moods is adaptive in threatening situations, their predominance in a benign life situation impedes adaptation (Figure 2). Likewise, the predominance of a positive mood in a threatening situation is also pathological (Figure 3). An inability to adequately discriminate, shift, and experience the mood which is adaptive, resulting in failures that invariably leads to predominance of adversive mood states such as fearful obsessiveness, phobias, panic, and depression.

Dysfunction of the brain stem and hypothalamus is associated with dysfunction of the allocation of somatic resources resulting in impairments of vegetative functioning (i.e. sleeping, eating, sexual functioning, temperature control, circulation, physiological responsiveness to stress and immune function). Cognitive, emotional and vegetative functioning are all interactive systems. A dysfunctional interaction of these systems can result in pathological behavior that impairs adaptation in the current environmental situation.

Within the nervous system, psychopathology correlates with the combination of a dysfunction of neurochemistry, altered neural architecture and altered gene expression. Conversely, therapeutic intervention correlates with a normalization of neurochemistry, neural architecture, and gene expression.

It is important to make the distinction between psychiatric syndromes vs. the cause of these syndromes. For example, major depression is one of many psychiatric syndromes of dysfunction. It appears to be caused by a complex interaction of genetic and other vulnerabilities and a life situation possibly requiring a certain time sequence. In other instances, the same vulnerability on the same stressful life situation may contribute to causing totally different psychiatric syndromes, or no disease state dependency upon the impact of other contributory factors.

When there is a dysfunction of the nervous system, we can partially compensate with conscious free will. However, there are limits in our capacity to compensate for some psychic or somatic limitations and impairments. It is necessary to emphasize the difference between syndromes of dysfunction and causes of pathology. Depression shall be discussed as an example of a syndrome of dysfunction, while one significant cause of mental pathology shall be discussed in Microbes and Mental Illness.

Disease is often comorbid with other related disease entities, leading to interactive disease states. Therefore, we cannot view a disease process as a closed system. Instead, we must understand the interaction of comorbid disease processes, some of which are full syndromal and others, which are sub-syndromal. The comorbidity may be somatic/somatic, somatic/psychic, or psychic/psychic. Somatopsychic disease is caused when physical (somatic) distress causes mental (psychic) illness. Conversely, psychosomatic disease is caused when psychic distress causes somatic illness.

Assessment

Sir William Osler, the father of American medicine, stated: " If you listen long enough, the patient will give you the diagnosis." We need to always retain our roots in old-fashioned, traditional medicine.

Assessment is performed by:

Taking a thorough and relevant history

Performing a thorough and relevant exam

Ordering and interpreting laboratory tests in the proper context

Exercising sound clinical judgment by someone trained in a field relevant to the patient's complaints.

We therefore need to recognize the patient's unique situations and examine them in a relevant manner. In psychiatry, much of this assessment is performed by a thorough examination. Many screening protocols exist, but these are rough screening tools and require follow-up individualized assessment.

Treatment

" Where there is love of humankind, there is also love of the art of medicine." *

The goal in treatment is to stop and reverse the pathological vicious cycles. The better we understand the sequence of events that causes and perpetuates the pathological process, the more options we have for treatment. Theoretically, we can intervene at any stage in the sequence of events that causes and/or perpetuates the disease process.

Most psychiatric illness is a complex vicious cycle with many entry points and, likewise, many exit points. To some degree, problems caused by environmental factors are often treated by environmental treatments; neurochemical problems by neurochemical treatments, etc. However, this is not always the case. Any safe and effective treatment that breaks the vicious cycle of disease may be implemented regardless of what initiates or perpetuates the disease. All situations are unique and individualized treatment plans are always required.

All treatment decisions are a complex, multi-system, weighted judgment attempting to predict and compare the benefits and risks of treatment against the risk of disease. Which is greater? No one can guarantee 100% predictability.

Prior treatments were crude when compared to those implemented today. The goal is to intervene in the most limited and effective manner. For example, in psychopharmacology, the older medications had many unwanted side effects in order to achieve a more limited therapeutic effect. The newer treatments, by comparison, have a more limited effect. To compare to a military model, the older treatments are like the carpet bombing of Dresden, while newer treatments are more like the smart bomb that was dropped down the chimney of military headquarters in the Gulf War. Although a highly targeted intervention is the goal, it is never fully achieved.

As a result of new technology, much progress has been made in the past few years to improve the treatment of mental illness. This improvement, including the new broad-spectrum psychotropics, has resulted in a reduced census in our psychiatric hospitals similar to the reduction in state hospital censuses after the release of Thorazine in the 1950's. Stigma, lack of awareness, health care system failures and financial barriers are the main obstacles to treatment today.

Once it is determined that treatment is needed, who has the responsibility and power to select the treatment option? Clearly, there should be a system of proportionate responsibility and power with those who hold the greatest responsibility having the greatest power in the treatment decision-making process. From an ethical standpoint, therefore, the patient (or the patient's caretaker) should have the greatest responsibility, second is the expertise of the treating physician and third are ethically accountable regulators.

In some deceptively complex health care systems, the patient and treating physician still hold the responsibility but lack the power to make effective treatment decisions. The entity (or individual(s)) who hold this power may be biased by various financial intents and may not put the interests of the patient first. In such cases, "therapeutic equivalents" and/or "therapeutic substitutions" denial of treatment or reduction of treatment, are used at the expense of the patient to improve profits for the "managing" company.

The term "therapeutic equivalent" implies the substituted therapy is equivalent, but is it? Given the complexity of disease, no therapy is truly equivalent. The very use of this term is fraudulent if it cannot prove the "therapeutic equivalent" is totally equivalent in every respect, in any given situation. "Therapeutic substitution" is a more honest term since it does not imply the substituted therapy is equal. The patient should hold a proportionate power and responsibility in making such decisions.

Many crude and rough treatment algorithms have been proposed and are sometimes used. If they are recognized to be teaching tools and very rough guidelines they may have value. If, however, they are used as a closed-system treatment protocol to override the uniqueness of the situation or sound judgment, they become reckless, negligent and dangerous. Patients and caretakers should use caution when being referred to or by an entity influenced by bias.

Access to Health Care

Access to health care is maintained by constant vigilance. It is impacted by many other issues such as trust that health care will be adequately controlled by medical ethics, a guarantee of confidentiality, protection of individual freedom, cost-effectiveness, protection against fraud and standards to maintain quality of care. Any effective plan must embrace all of these areas.

There has been a failure to provide an adequate plan in our country. As a result, profit-driven systems such as managed care have proliferated and have clearly failed to meet the needs of our society. Capitated plans are a slight improvement over managed care because the plan administrators have a greater ethical commitment. However, they are limited potentially since there is an inherent conflict of interest between the needs of the patient and that of the provider.

Combinations of medical savings accounts, fee for service, traditional indemnity and other plans continue to have potential. In my opinion, proportionate responsibility is a critical issue. All who participate must have proportionate levels of responsibility and power to maintain an adequate balance of power and accountability in the health care system. Parity of mental health coverage is also critical. If we fail to propose an effective health care plan, others have, and will continue to propose plans that are self-serving.

As a member of the American Psychiatric Association Committee for Universal Access, I am gathering information relevant to health care access. I am looking for ideas and advice for the construction and proposal of a fair and effective health care plan. This is not a forum for grievances but an opportunity for you to participate in building a health care plan that is ethical and cost-effective, with the interests of the patient first.

The amount of resources allocated from the total budget towards health care is dependent upon our perception of the value of life. Since we, as a society, agree to pay for our own and other's health care, how can we be assured this money is well spent on true health care rather than being wasted on bureaucracy and fraud? What is a fair and effective system to allocate health care dollars?

Treatment Decisions

The patient and/or their guardian have the authority to consent to treatment decisions. In making these decisions it is necessary to listen carefully to the opinion of the treating physician. In all medical decisions, no one has any total ability to predict the future. All decisions are based upon a weighted decision comparing the risks of treating vs. not treating. Untreated or inadequately treated illnesses may sometimes have complex and far reaching effects. Conversely, any treatment that may have desirable effects may also have undesirable side effects as well. Since everyone is different, various treatments may have a therapeutic or undesirable side effect in different individuals. Studies are preformed to assess safety, tolerability and therapeutic effects in a significant number of patients. Since no two people are exactly the same, no prior study can totally predict a response in any given individual. Occasionally some side effects are evident only after many have been treated for long periods of time. There are many sources of information, some being more reliable than others. In considering treatment options and consenting to treatment decisions, feel free to investigate all sources of information. One source of medical information is the peer reviewed medical literature, some of which is available through the National Library of Medicine at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov Other sources of information include consulting other physicians or practitioners, the Physician’s Desk Reference, the FDA, the Internet and various media outlets. It is important to note that most medical knowledge is yet to be discovered, and there is a considerable amount of conflicting information within the current medical literature and other sources of information.

For a variety of reasons, there has been an increasing motivation for individuals and groups to impact the physician patient relationship. This has sometimes resulted in a variety of media reports, insurance company policies, bureaucratic obstacles, privacy intrusions and various high profile lawsuits.

It is suggested all this information be approached in a manner which recognizes the potential bias from each source in an effort to maintain scientific objectivity. You have the ultimate authority in making decisions regarding your health. Open communication with your treating physician regarding beneficial as well as undesirable effects is encouraged to help achieve a better outcome.

Infectious Disease and Mental Illness

A significant amount of disease and mental disease may have an infectious disease component to the pathological process. The evidence to support this is a combination of insights from theoretical biology (particularly Darwinian medicine), an expanding database of medical research and direct clinical observations.

In my clinical experience, the link between psychopathology and infectious disease has been an issue with Lyme disease, syphilis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, mycoplasma pneumonia, toxoplasmosis, borna virus, AIDS, CMV, herpes, strep and other unknown infectious agents.

The combination of chronic stress and chronic low-grade infectious disease is a frequently seen dynamic. Disease begins with vulnerability and an exposure to one or more stressors. The vulnerability may commonly include genetic and/or increased vulnerability as a result of chronic stress. As a result of these and other vulnerabilities, the microbe more easily penetrates the host's defenses and an initial infection may then occur. The course of the infection most relevant to psychiatry would be chronic, low-grade, persistent infections or the persistence of the infectious agent in the inactive state. At a later point in time, some triggering event(s) (i.e.: chronic stress or other infectious agents), may then cause the activation of the infectious agent(s) and the progression of the pathological process. Neural injury may occur by a variety of mechanisms, which include vasculitis, direct cell injury, inflammation, autoimmune mechanisms and excitotoxicity. This injury leads to a vicious cycle of disease resulting in dysfunction of associative and/or modulating centers. Injury to associative centers more commonly causes cognitive symptoms, while injury to modulating centers more commonly causes emotional and allocation of attention disorders. In some cases, the infection and injury may occur before birth.

In my collective database of patients demonstrating psychiatric symptoms in response to infectious disease, the majority of the cases has been infected by Lyme disease and quite often co-infected with other agents. Psychiatric syndromes caused by infectious disease in my database most commonly include depression, OCD, panic disorder, social phobias, variants of ADD, impulse control disorders, bi-polar disorders, eating disorders, dementia, various cognitive impairments, psychosis and a few cases of dissociative episodes. In the more obvious cases, symptoms are present with cognitive, neurological and physical signs. Laboratory tests are sometimes, but not always, able to confirm the diagnosis.

Depression

Let us look at clinical depression as an example of a pathological vicious cycle. Clinical depression is associated with two modulations occurring simultaneously and chronically, dysphoria and the generalized stress response.

Dysphoria is a modulation that is part of the harm perception/avoidance axis. This is an emotion we all feel when we perceive a futility in our current behavior and experience disappointment.

In contrast, we experience anger and aggression when the disappointment is perceived as being caused by an external source. When the disappointment causes dysphoria, the modulation shift increases behavioral inhibition, increases anticipation of harm, increases harm avoidance, increases introspection, decreases exploration of the environment, decreases reactivity to external stimuli, decreases appetite for food and decreases sexual appetite.

In short, it coordinates functions that allow us to retreat, introspect and to redirect our efforts in a more effective direction. In this instance, dysphoria facilitates adaptation to disappointment.

If, however, we can not find other behavioral alternatives, then there is an increasing level of stress and modulations that are part of the stress response systems. The stress response modulation is a shift in the allocation of resources. Stress pre-empts other functions that are less critical for immediate survival. Modulation shifts include vigilant arousal, focused attention on the negative, a shift to sympathetic tone, increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and altered cardiovascular tone. Resources are allocated away from growth, immune functioning, sexual functioning, digestion, regeneration and other mental processes.*

There are multi-systems simultaneous changes that are molecular, genetic transcription, cellular, synaptic, neurochemical, neural network, neurohormonal, autonomic, hormonal, psychological, behavioral and social. We can adapt and thrive in response to episodes of short-term stress, followed by an episode of reduced stress in which responses can be allocated to other functions. In contrast, chronic stress depletes other functions and can lead to a pathological vicious cycle. The chronic generalized stress response alters neural functioning by changing the long-term potential of neurons. The structure of these pathways alters adaptation. With repeated episodes of a pathological state, the brain is sensitized to be more prone to display that state. All of these changes contribute to the vicious cycle of clinical depression. In some cases, counter regulating mechanisms serve a feedback function, which prevents the vicious cycle. Some susceptible individuals, however, lack these counter-regulating systems.

There are many entry points into the vicious cycle of depression and, likewise, many exit points from this pathological cycle. We can treat depression by intervening at any of the many systems that are part of the cycle. However, in any given individual, different triggers are more significant than others are. Intervening in the system that is most critical in the vicious cycle is the key to successful treatment. The question in any individual depression is what system drives the pathological process and which are more of a ripple effect and less critical in perpetuating the pathology? Every individual is different and every depression is different as well. Unipolar depression shows cycles that alternate between episodes of normal functioning and episodes of depression with behavioral inhibition. Bipolar depression shows cycles that alternate between episodes of normal functioning, depression with behavioral inhibition and mania with behavioral stimulation. Just as there is a behavioral inhibition circuit, a behavioral stimulation circuit exists which is highly active in a hypomanic and manic state.

Since depression can often follow a failure to adapt, it may be secondary to some other pathological state or an adaptive failure. These primary comorbid illnesses may be physical, mental, social and/or otherwise. (See Diagrams: Depression, Dysphoria, Dysphoria Modulation, Stress and System Hierarchy of Factors Which May Drive Depression)

The Assessment of Depression

The core symptoms of clinical depression are modulation changes associated with emotional (limbic) and vegetative (brain stem/hypothalamic) modulation changes.

Core screening questions are:

Emotional Modulation:

Is there more dysphoria than is appropriate for the current life situation?

Is there less capacity for pleasure for the daily activities of life than is appropriate for the current life situation?

Vegetative Modulation:

Is there a decline of normal eating patterns with abnormal patterns of appetite, satiation and food intake? Is there a decline of normal sleeping patterns with a loss of the normal 24-hour circadian rhythms resulting in not being well rested in the morning?

Is there a decline of normal sexual functioning with a loss of normal interest and sexual functioning?

Modulation of Perception:

Is there a disproportionate focus on negative perceptions?

Modulation of Motor Functioning:

Is there an abnormal pattern of motor functioning such as psychomotor retardation (diminished physical activity) or agitation?

Modulation of Processing:

Is there excessive preoccupation on negative/adversive thoughts?

If symptoms are present in these areas, a more thorough evaluation should then be performed with an assessment of the contributing factors in each system that can contribute toward depression.

The Treatment of Depression

A combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants are the most common treatments for depression, although a very large number of different treatments exist. Antidepressant treatments are most commonly implemented when the vegetative symptoms of depression are present. Studies show that any one antidepressant is effective in about 70% of patients. A large number of medications are FDA approved for the treatment of depression and many medications which are not formally approved are sometimes used to treat depression. The goal is to select the treatment that is most effective and best tolerated for that individual.

Since depression most commonly is comorbid and interacts with other somatic and mental diseases, the treatment of comorbid disease is a major consideration in choosing the most effective treatment. The newer, broad-spectrum psychotropics are often quite effective in treating both depression and comorbid/interactive mental illnesses. It is, therefore, a very individualized decision based on a thorough, confidential assessment.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

As described, depression begins with an adaptive modulation, which then becomes extreme, evolving into a pathological vicious cycle; many loops are interconnected with failure of counter-regulatory (feedback) systems. Likewise, other pathology in the harm avoidance pathway can be explained in a similar manner. Much of what is currently called Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder can be viewed as an excessive modulation shift in anticipation, often the anticipation of harm, driving thoughts and behaviors in that direction. Obsessive-compulsive patients often describe a period in the beginning of their illness when they first experience an excessive amount of the emotion of anticipation of harm. The forcefulness of this emotion then drives thought content and imagery towards harm-related subjects. Behaviors, habits and compulsions are also driven towards what is perceived to be harm avoidance conduct. There appears to be an imbalance between the pathways that drive anticipation of harm and the feedback pathways, which inhibit this function.

Compulsions are repetitive behavioral patterns that are a result of activity of the motivational system. For example, checking rituals are compulsions to relieve obsessions of pathological self-doubt, while cleaning rituals are compulsions to relieve obsession of contamination. Besides obsessions, there are other causes of compulsions. Some compulsions can be viewed as instinctual behaviors, i.e.: grooming, sex, nesting, hoarding, etc. Other compulsions are learned (habits) or instinctual behaviors, which are modified by learning.

Tics and other movements are repetitive movements, which are also a part of the motion-emotion basal ganglia system. Dysfunction of the basal ganglia or its cerebral connections is associated with OCD. Dysfunction of the adjacent cingulate gyrus is associated with compromising the flexibility of response. In all probability, apathy is associated with a loss of activity of a stimulatory center, while obsessions, intrusive images, compulsions and tics are associated with a loss of activity of inhibitory centers. Excessive allocation of mental resources in these directions then results in pathological vicious cycles and the illness of obsessive-compulsive disorder.*

Panic Disorder

Panic is triggered by a perception of imminent harm. There is a rapid acceleration of the alarm reaction. Thus, individuals with the illness of panic disorder find this pathway triggered too readily by events that may not warrant such a level of alarm. The counter regulating mechanisms fail to dampen the speed of acceleration of the alarm reaction. Any fear can potentially trigger a panic attack in a sensitized individual. Once someone experiences panic attacks, there is then fear of the cues associated with triggering the panic attack, as well as a fear of the attack itself. Once fear is triggered in a susceptible individual, they are increasingly sensitized to the fear and the vicious cycle of fear, which ensues. This process occurs in multiple systems simultaneously. The fear of the panic attack or the fear of the fear is often greater than the fear of the cues, which are associated with triggering the attack.

Like depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, this may be another condition in which stimulatory pathways are out of balance with inhibitory pathways. Although pathology is caused by an imbalance of opposing stimulatory and inhibitory pathways, overactivity of a stimulatory center (as seen in a complex partial seizure disorder) is a less common cause of pathology. More commonly, there appears to be a failure of normal inhibitory (or feedback/counter-regulatory) control.

Fear

Fear can be evoked by a variety of triggers. (See diagram: Fear Sequence). We are hypophobic if fear is not strong enough given the threat that exists. In contrast, we are hyperphobic if fear is excessive. Many fears are instinctually pre-programmed, i.e.: fear of physical harm, heights, closed spaces and many interpersonal fears. In addition, learning also affects the nature of our fears. A simple learned fear occurs when we associate something with harm. When the learned fear is disproportionate to the threat, it is termed a simple phobia. These learned fears may either increase or be separate and unrelated to instinctual fears. In either case there is excessive fear and difficulty discriminating the level of threat posed by certain cues.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder has some similarities to a simple learned phobia. Both are learned fears, however, post traumatic stress disorder is far more complex. When a traumatic event causes a posttraumatic stress disorder, the threat is less predictable, often involving trust assessment, and there is a greater level of fearful helplessness leading to a greater perception of vulnerability. The very high emotional arousal associated with this memory is difficult to process and integrate with other memory. As a result, the memory is not processed but instead is suppressed and repressed, disconnected from other memory and remains in an intensely undifferentiated emotional and painful form. This finding is demonstrated on PET and SPECT scans. Keeping the memory suppressed causes a significant change in coping mechanisms including avoidance, persistent fearful arousal and emotional numbing which further impair the capacity to adapt and contribute to retraumatization. The psychological changes further contribute to neurochemical and neuroanatomical changes. These changes lead to a pathological vicious cycle that results in the signs and symptoms associated with PTSD. In both PTSD and learned simple phobias there is an inability to extinguish a learned fear. Arginine-vasopressin is one of many neuromodulators associated with PTSD and inhibits the extinction of a learned fear. */**

Arginine-vasopressin inhibits the extinction of a learned fear. Excessive activity of this pathway may contribute to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Anorexia Nervosa disorder, another learned fear, is also associated with elevated arginine vasopressin. posttraumatic Stress and anorexia show many similarities; anorexia nervosa may be viewed as a type of posttraumatic stress disorder. Both illnesses are associated with a genetic vulnerability.

PTSD contributes to a significant amount of emotional distress, disability, impulse behavior and physical symptoms. The most concise, current review of PTSD is by B. van der Kolk, The Psychobiology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, J Clin Psychiatry.; 1997; 58 (sup 9) p. 16-24.